If you’ve ever wondered why:

Your knees cave in at the bottom of a squat

Your low back extends when the weight gets heavy

One hip always feels “stuck” at 90°

Or mobility drills don’t seem to transfer to strength

…you’re probably running into a concept explained by the Limb Arc Model.

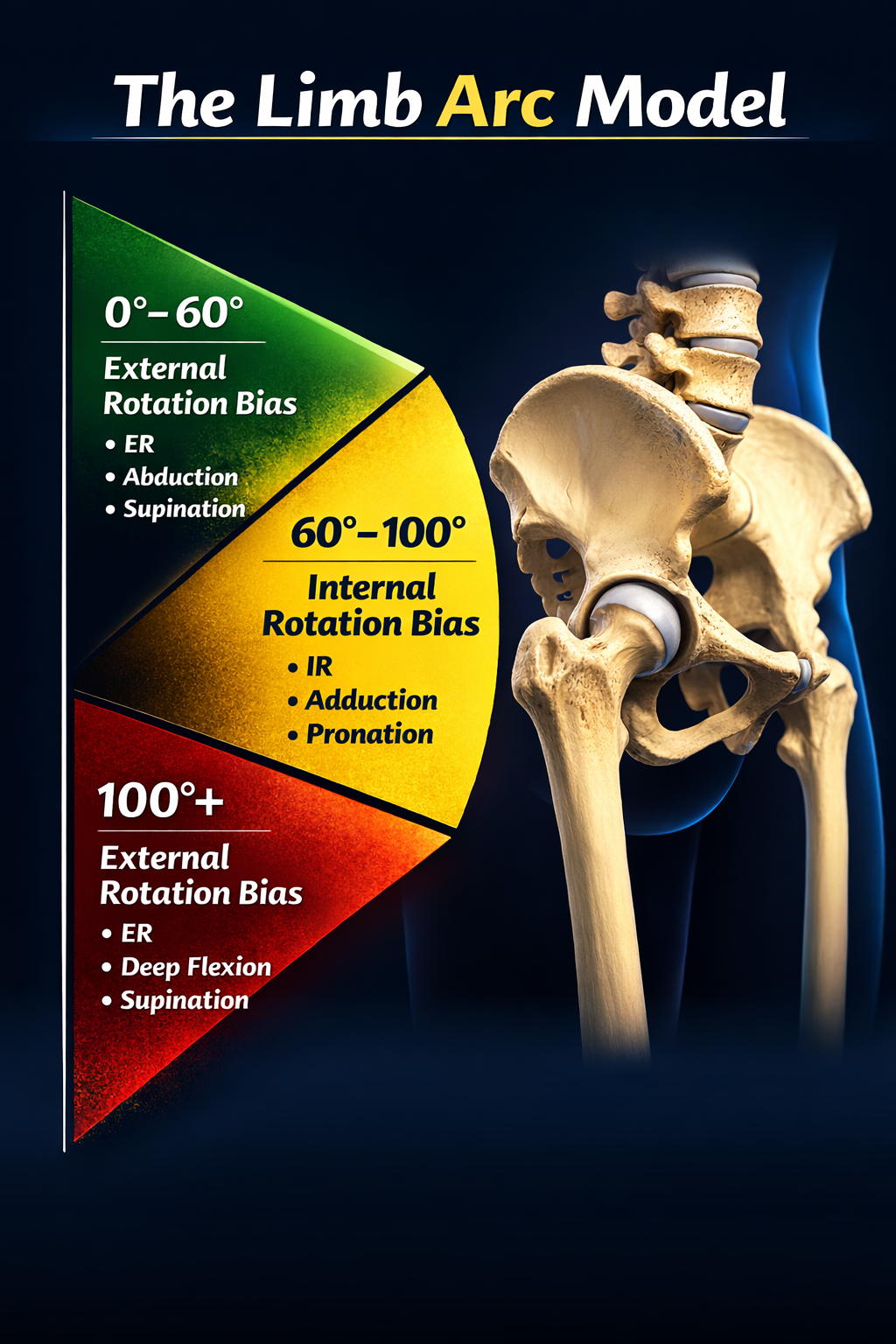

This model, commonly attributed to Bill Hartman, describes how rotational bias changes across ranges of joint flexion — particularly at the hip. And once you understand it, exercise selection becomes dramatically more logical.

Let’s break it down.

What Is the Limb Arc Model?

The Limb Arc Model proposes that rotational leverage changes as a joint moves through flexion.

At the hip specifically:

Early flexion favors external rotation (ER)

Mid-range flexion favors internal rotation (IR)

Deep flexion returns to an external rotation bias

This is not arbitrary. It reflects changes in joint geometry, length tension relationships, and moment arms.

Most people train hip flexion as if it is one continuous quality. It is not. It is three mechanically distinct regions.

That shift matters for:

Squats

Deadlifts

Split squats

Gait mechanics

Sport performance

Injury risk

The Hip Flexion Arc Explained

Here’s the simplified breakdown:

0–60° Hip Flexion → External Rotation Bias

In early hip flexion, the joint favors:

External rotation

Abduction

Supination at the foot

Sacral counternutation

In gait, this corresponds most closely with early stance, when the heel has contacted the ground and the pelvis is relatively externally rotating as load is being accepted.

In the gym, this is the top portion of a squat or the early phase of a hinge.

External rotators and abductors have favorable leverage here.

60–100° Hip Flexion → Internal Rotation Bias

Around 90° hip flexion:

Internal rotators and adductors have improved leverage

Length–tension relationships favor IR

The piriformis shifts moment arm toward IR

The sacrum moves toward nutation

The foot transitions toward pronation

In gait, this corresponds most closely with mid stance, when the pelvis is internally rotating on the femur and vertical ground reaction forces are highest.

In a squat, this is typically around parallel.

100°+ Hip Flexion → Returns to External Rotation Bias

As you approach deep hip flexion:

The system transitions back toward ER

Supination strategies often reappear

External rotators regain leverage

This helps explain why some people feel “better” deep in a squat even if they struggle at parallel. They are returning to a range where external rotation leverage increases again.

Why Internal Rotation at 90° Matters

Most loaded bilateral lower-body exercises demand control around 60–100° hip flexion.

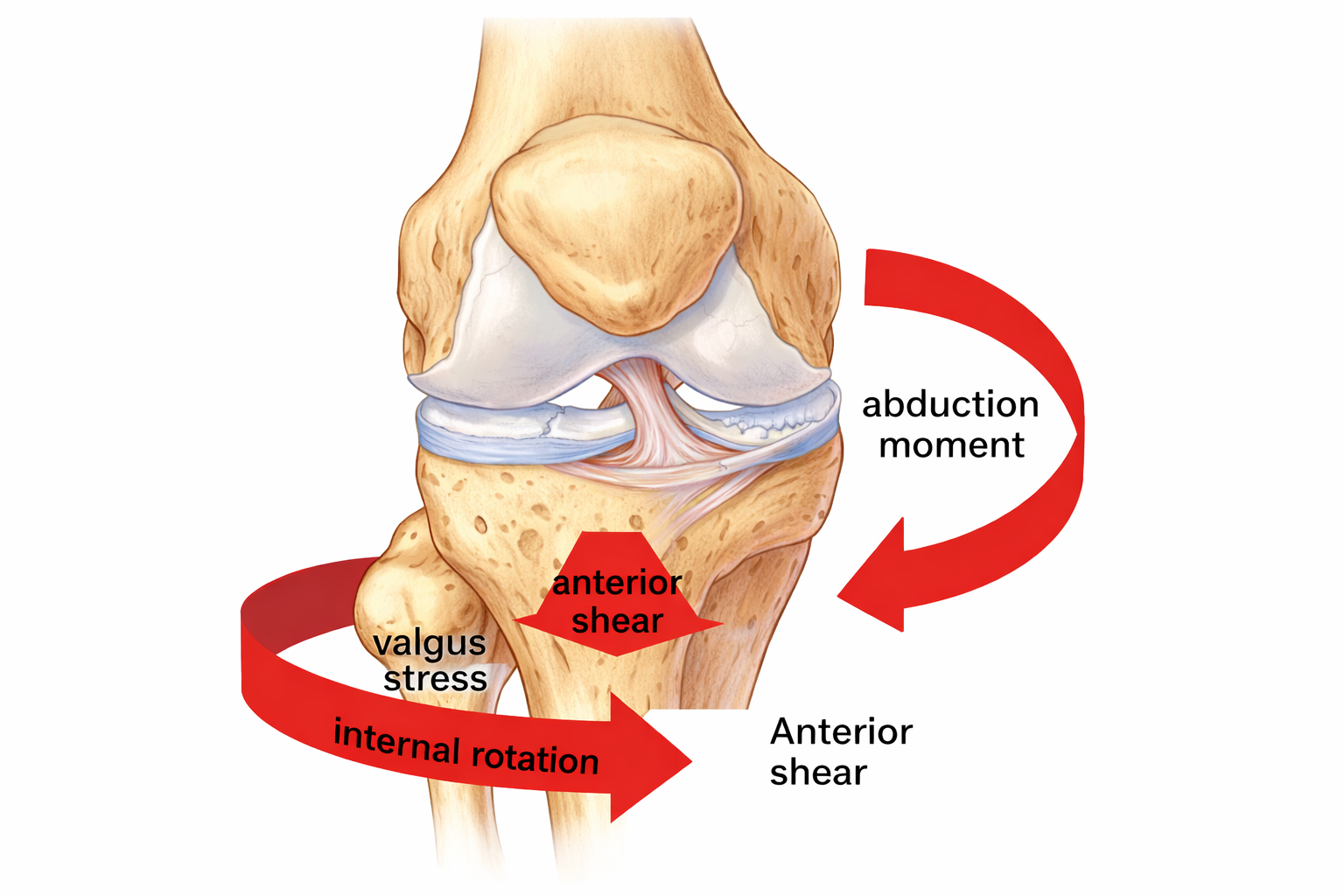

If internal rotation is limited in that range, common compensations show up:

Knee valgus

Lumbar extension

Butt wink

Hip shifting

Over-pronation

Gripping with toes

This is not always a strength problem.

It’s often a relative motion problem.

The joint is being asked to produce force in a range it does not control. When the femur is not internally rotating relative to the pelvis, the pelvis, spine, or foot moves instead.

“Train within the Range You Own”

Here’s where this becomes practical.

Owning a range means:

You can access it

You can control it

You can breathe in it

You can maintain joint relationships without compensating

If you lack IR at 90°, loading it heavily won’t fix it.

It may:

Reinforce compensations

Drive orientation strategies (like anterior pelvic tilt)

Increase compressive strategies instead of restoring motion

Instead, you might need:

Split squats that bias mid-stance

Exercises emphasizing medial arch contact

Internal rotation control drills

Breathing-based repositioning work

Heel references to restore early stance mechanics

Force production should follow motion restoration — not precede it. Ie; Restore control first. Then add load.

How This Applies to Programming

The Limb Arc Model gives you a filter for exercise selection.

The question is not whether someone “has internal rotation.”

The question is where in the arc they lose control.

If Control Breaks Down Between 0 and 60 Degrees

You will see:

Difficulty accepting load at the top of the squat

Poor heel contact

Immediate external rotation gripping

Early lumbar extension

In this case, reinforce early stance mechanics.

Use closed chain drills that emphasize heel reference and controlled external rotation.

Keep the hip in the zero to sixty degree range and teach load acceptance without extension strategies.

The goal is stable external rotation control in early hip flexion.

If Control Breaks Down Between 60 and 100 Degrees

You will see:

Knee valgus at parallel

Hip shift at ninety degrees

Lumbar extension at the sticking point

Loss of medial arch control

This is the most common presentation.

Here, you bias time spent in sixty to one hundred degrees of hip flexion in closed chain.

Split squat variations are useful when organized correctly because they allow:

Pelvis on femur relative motion

Clear stance leg reference

Control of hip flexion angle

Moderate load that does not overwhelm internal rotation capacity

The key is managing support and load so that the pelvis can internally rotate on the femur without defaulting into orientation strategies such as anterior pelvic tilt or lateral shift.

This is not about making someone balance harder.

It is about placing them in the internal rotation biased window and allowing them to control it.

If Control Breaks Down Beyond 100 Degrees

You will see:

Instability or collapse in deep squat

Over reliance on passive structures

Loss of tension in the bottom

In this case, gradually expose the athlete to deeper flexion under controlled conditions, restoring external rotation leverage without compensatory lumbar flexion.

Why This Model Is Powerful

The Limb Arc Model connects:

Gait

Breathing mechanics

Pelvic motion

Squat depth

Performance

Compensation patterns

It explains why:

One depth feels strong and another feels unstable

Deep squats don’t fix mid-range weakness

“Mobility” doesn’t always transfer to strength

Because leverage changes as joint angles change.

And if you don’t own the transition between those zones, the body will compensate.

Final Takeaway

The Limb Arc Model isn’t about stretching more.

It’s about understanding that:

Rotational demands shift as joints move through flexion.

And if you load a range you don’t own, your body will borrow motion from somewhere else.

Train the range you control.

Then expand it.

That’s how you build durable strength.

Learn more about how we assess movement and build individualized programs at Avos Strength.