Written by Michael Crawley, BSc, BPT, CSCS

BACKGROUND

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries (ACLI) are often viewed as sudden, unavoidable events that are “fixed” through surgery. In reality, both injury risk and long-term outcomes are strongly influenced by training quality, rehabilitation approach, and the decisions made before and after injury.

This article highlights the complexity of ACL injuries, explains how and why they occur, and outlines key training and rehabilitation considerations that influence risk and return to sport outcomes. While ACL injuries are often discussed in isolation, they are rarely simple knee injuries, and successful outcomes require a broader, long-term view.

The information presented is intended to provide practical, actionable insight for a range of athletes and stakeholders, including:

Youth multi-sport athletes and their parents

High-level collegiate and professional athletes

Competitive recreational athletes of all ages

ACLI have increasingly been described as an epidemic across both amateur and professional sport. Several studies report that ACL injuries account for approximately 50 percent of knee injuries. Over the past 10 to 20 years, female and youth athletes have experienced the largest increase in incidence. Childers et al. (2025) identified female adolescent athletes as the highest-risk group, with a 1.5-fold increased risk compared to their male counterparts.

Importantly, ACL injuries often occur alongside meniscal and cartilage damage. These associated injuries substantially increase the risk of long-term joint degeneration, including osteoarthritis and the need for total knee replacement (Petushek et al. 2019). This added complexity also plays a significant role in surgical decision-making and long-term outcomes.

HOW DOES THIS HAPPEN

ACL injuries generally fall into two categories:

Contact injuries

Non-contact injuries, which account for nearly 80 percent of all ACL ruptures (Beaulieu et al. 2023)

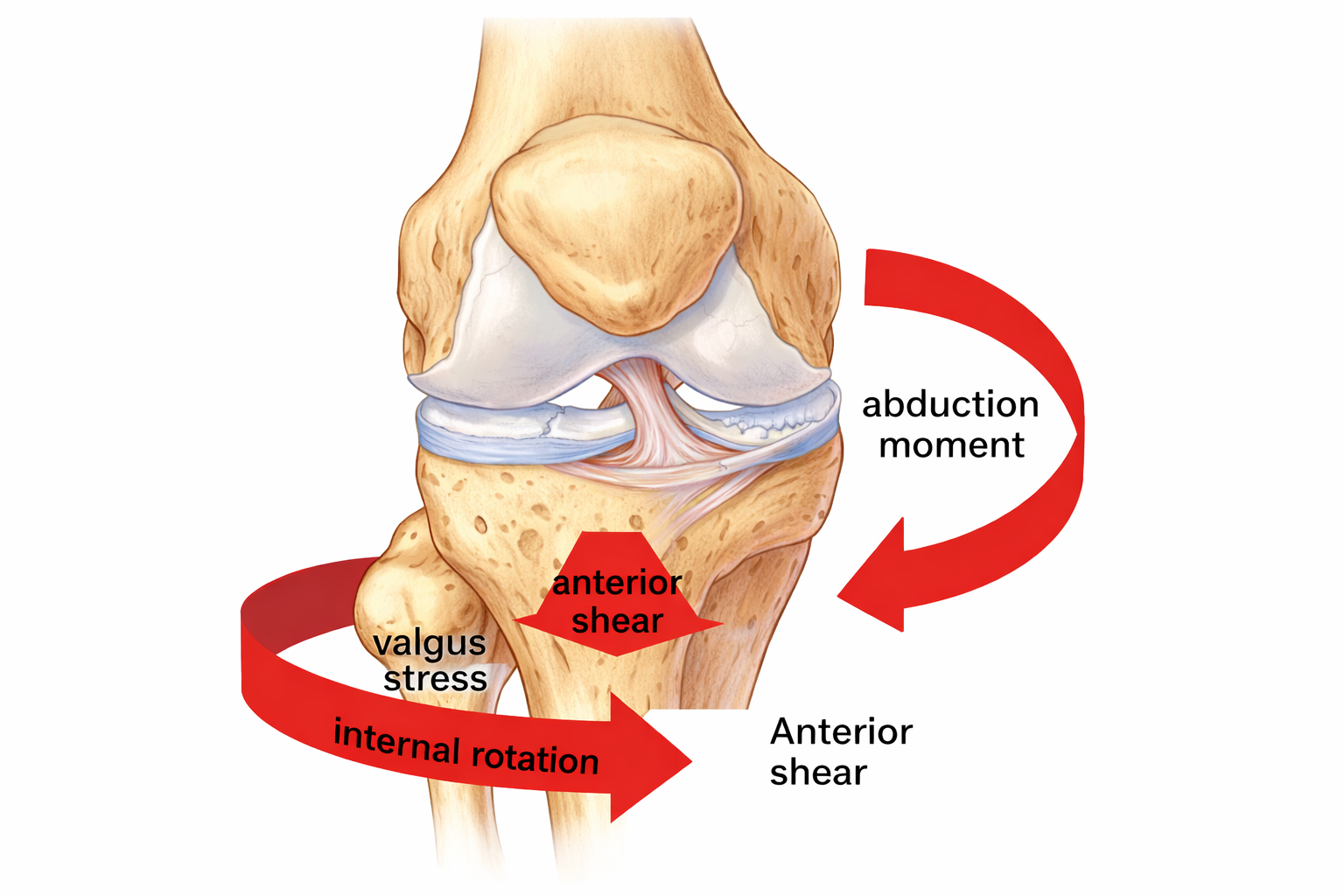

Most non-contact injuries occur during high-speed or high-load movements such as single-leg landings, rapid deceleration, or sharp changes of direction. These movement patterns are common across many sports and can occur both during high-intensity competition and through repeated lower-intensity exposures over time.

Sports such as basketball, soccer, netball, and rugby place consistent demands on these movement patterns, emphasizing the importance of preparing athletes not only for isolated high-risk moments, but also for cumulative loading over a season.

RISK FACTORS AND TRAINING IMPLICATIONS

ACL injury risk is influenced by a combination of anatomical, biomechanical, and training-related factors. While some risk factors cannot be changed, many can be meaningfully influenced through education and training.

Female Athlete Considerations

In female athletes, structural features of the tibia, such as posterior tibial slope, along with hormonal influences on ligament laxity, contribute to an increased risk of ACL injury (Kikuchi et al. 2022; Beaulieu et al. 2023).

While these factors cannot be modified, they highlight the importance of early education for young female athletes and their coaches. Building awareness around neuromuscular control, strength development, and movement quality is a critical component of risk reduction.

Playing Surface

Research examining the influence of playing surface has produced mixed findings. However, some studies report higher ACL injury rates in NFL athletes competing on artificial surfaces compared to natural grass (Hershman et al. 2012).

Although athletes cannot always control the surface they compete on, training exposure can be diversified. Incorporating training on a variety of surfaces may help improve adaptability and tolerance to different loading conditions prior to competition.

Fatigue and Repetitive Loading

Emerging evidence suggests that ACL rupture does not always result from a single traumatic event. Fatigue and repetitive sub-maximal loading may contribute to progressive ligament failure over time (Wojtys et al. 2016).

From a training perspective, building tissue capacity in key muscle groups such as the hamstrings, quadriceps, calves, and adductors may increase tolerance to repeated stress and reduce injury risk.

Whole-Body Strength and Neuromuscular Control

Although ACL injuries occur at the knee, load can be transmitted from both the top down and bottom up through the kinetic chain. Poor three-dimensional strength across the trunk, hip, knee, and ankle can increase stress on different portions of the ACL (Beaulieu et al. 2023).

Training that develops strength in multiple planes of motion, both in isolated exercises and integrated movement patterns, helps improve robustness and neuromuscular control.

For example, multi-directional jumping exercises can target trunk, hip, knee, and ankle coordination simultaneously:

Jumping exercise example: https://youtu.be/foi2J2Tpks8

WHAT IS CONSIDERED SUCCESSFUL ACL REHABILITATION AND HOW IS IT ACHIEVED

Over the past decade, the definition of successful return to sport (RTS) following ACL injury has evolved. A well-regarded Canadian kinesiologist, Carmen Bott, emphasizes that simply returning to sport is not the same as returning successfully.

Long-term data highlight the difficulty of maintaining sport participation following ACL injury. Pinheiro et al. (2022) reported that among elite athletes followed over five years, participation at the same competitive level declined from 75 percent in year one to just 20 percent by year five.

Outcomes are even less favorable in competitive amateur athletes. Approximately 65 percent return to pre-injury level, with overall return to competitive sport roughly 10 percent lower (Nwachukwu et al. 2019).

Following a well-structured, progressively loaded strength and conditioning program can enhance both physical capacity and confidence during rehabilitation. A simplified progression may include:

Heel slide + straight leg raise (early post-surgery): https://youtube.com/shorts/MyEWyGisbug

Wall squat (introducing controlled strength): https://youtube.com/shorts/M2ZhZGdo11Q

Drop squats (early preparation for landing mechanics): https://youtube.com/shorts/MW-KZrf18RU

Nordic hamstring exercise (high-level strength development): https://youtube.com/shorts/4YNp9C0PQ_4

Full-range jumping progressions: https://youtube.com/shorts/lDO7zvvshUo

This progression represents only a snapshot of a rehabilitation process that commonly spans 9 to 12 months. Progression should be goal-oriented rather than time-driven, with athletes meeting clearly defined prerequisites before advancing.

TO CUT OR NOT (NOT MEDICAL ADVICE)

When an athlete is diagnosed with an ACL injury, the immediate assumption is often that surgery is required. Indeed, 98 percent of orthopaedic surgeons recommend ACL reconstruction for athletes aiming to return to sports involving running, cutting, and jumping (Weiler et al. 2015).

However, surgery is not always the appropriate choice. Non-operative management may be suitable depending on several factors (Komnos et al. 2024), including:

Individual expectations and current sport level

Presence of concomitant injuries such as meniscal or cartilage damage

Degree of knee laxity and perceived instability

Fitzgerald et al. (2000) classified individuals into three groups:

Copers: return to pre-injury level of sport

Adapters: return to a reduced level to avoid instability

Non-copers: unable to return due to persistent instability

A notable example is a Premier League footballer who returned to play eight weeks after a complete ACL rupture without surgery (Weiler et al. 2015). While this represents a single case, it highlights the importance of individualized decision-making.

What Does This Mean for Non-Professional Athletes?

Athletes outside professional systems should:

Ask detailed questions about the structures involved in their injury (ACL only vs associated damage)

Communicate subjective symptoms such as instability, confidence, or locking

Clarify long-term goals, whether returning to competition or maintaining an active lifestyle

Consider an initial period of structured rehabilitation before committing to surgery, particularly when instability is not present

In the Premier League case study, the athlete consulted three surgeons, two of whom recommended surgery, while one supported a conservative rehabilitation-first approach. This underscores the value of informed discussion and shared decision-making.

SUMMARY AND KEY TAKEAWAYS

ACL injuries are complex and influenced by multiple interacting factors including age, sex, sport demands, training exposure, and movement quality.

Educating female athletes about menstrual cycle considerations and ligament laxity may be beneficial.

Monitoring training load during high knee-stress activities is important.

Developing tissue capacity through comprehensive strength training can enhance tolerance to stress.

Returning to previous levels of sport remains challenging, particularly for non-professional athletes.

Rehabilitation should be thorough and guided by experienced practitioners.

Successful return to play depends on strength, neuromuscular control, and power that match sport-specific demands.

Surgery is not the only option.

Decisions should be made collaboratively between the athlete, physiotherapist, and surgeon.

Clear communication around injury extent and long-term goals leads to better outcomes.

Looking for Individualized Support?

If you’re currently dealing with an ACL injury, returning from surgery, or unsure how to safely progress your training, working with an experienced coach can make a meaningful difference.

Michael works closely with athletes across all levels and has extensive experience supporting ACL rehabilitation and return-to-sport training in collaboration with physiotherapists and medical professionals.

If you’d like to explore whether coaching support is right for you, you can book an initial assessment here.

PART 2: WHAT TO EXPECT

The next article will focus specifically on female and youth athletes and will explore:

Graft selection considerations when surgery is required

The role of prehabilitation in improving long-term outcomes

References

Beaulieu, M. L., Lamontagne, M., Xu, L., & Li, G. (2023). Loading mechanisms of the anterior cruciate ligament. Sports Biomechanics, 22(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2021.1916578

Childers, J. D., Weiss, L. J., Pennington, Z. T., Nwachukwu, B. U., & Allen, A. A. (2025). Reported anterior cruciate ligament injury incidence in adolescent athletes is greatest in female soccer players and athletes participating in club sports: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthroscopy, 41(3), 774–784.e772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2024.03.050

Fitzgerald, G. K., Axe, M. J., & Snyder-Mackler, L. (2000). A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 8(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001670050190

Hershman, E. B., Anderson, R., Bergfeld, J. A., Bradley, J. P., Shelbourne, K. D., Sills, A., & McGuire, K. J. (2012). An analysis of specific lower extremity injury rates on grass and FieldTurf playing surfaces in National Football League games: 2000–2009 seasons. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(10), 2200–2205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546512458888

Kikuchi, N., Hara, R., Hiranuma, K., Nakazawa, R., & Fukubayashi, T. (2022). Relationship between posterior tibial slope and lower extremity biomechanics during a single-leg drop landing combined with a cognitive task in athletes after ACL reconstruction. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 10(7), 23259671221107931. https://doi.org/10.1177/23259671221107931

Komnos, G. A., Kotsifaki, A., Dingenen, B., & Gokeler, A. (2024). Anterior cruciate ligament tear: Individualized indications for non-operative management. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(20), Article 6233. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13206233

Nwachukwu, B. U., Chang, B., Voleti, P. B., Berkanish, P., Cohn, M. R., & Allen, A. A. (2019). How much do psychological factors affect lack of return to play after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A systematic review. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 7(5), 2325967119845313. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967119845313

Petushek, E. J., Sugimoto, D., Stoolmiller, M., Smith, G., & Myer, G. D. (2019). Evidence-based best-practice guidelines for preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in young female athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(7), 1744–1753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518782460

Pinheiro, V. H., Mascarenhas, R., Saltzman, B. M., & Nwachukwu, B. U. (2022). Rates and levels of elite sport participation at 5 years after revision ACL reconstruction. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(14), 3762–3769. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465221127297

Weiler, R., Monte-Colombo, M., Mitchell, A., & Haddad, F. (2015). Non-operative management of a complete anterior cruciate ligament injury in an English Premier League football player with return to play in less than 8 weeks: Applying common sense in the absence of evidence. BMJ Case Reports, 2015, bcr2014208012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-208012

Wojtys, E. M., Beaulieu, M. L., Ashton-Miller, J. A., & Newcomb, W. (2016). New perspectives on ACL injury: On the role of repetitive sub-maximal knee loading in causing ACL fatigue failure. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 34(12), 2059–2068. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.23441